In 2013, the Riga Shipyard pompously celebrated its 100th anniversary. Presentations, ceremonies, banquets were organized, everything as we love. A wonderful album was published with the history of the factory, its achievements, its bright prospects. However, the prospects are still bright, but only on paper. In the latest financial statement of the company for the first half of 2019, its board proudly announces that it continues to improve financial flows, marketing activities, increase the number of ships to be repaired, and will continue to renovate the Company’s industrial buildings, floating docks, cranes, tugs and other fixed assets.

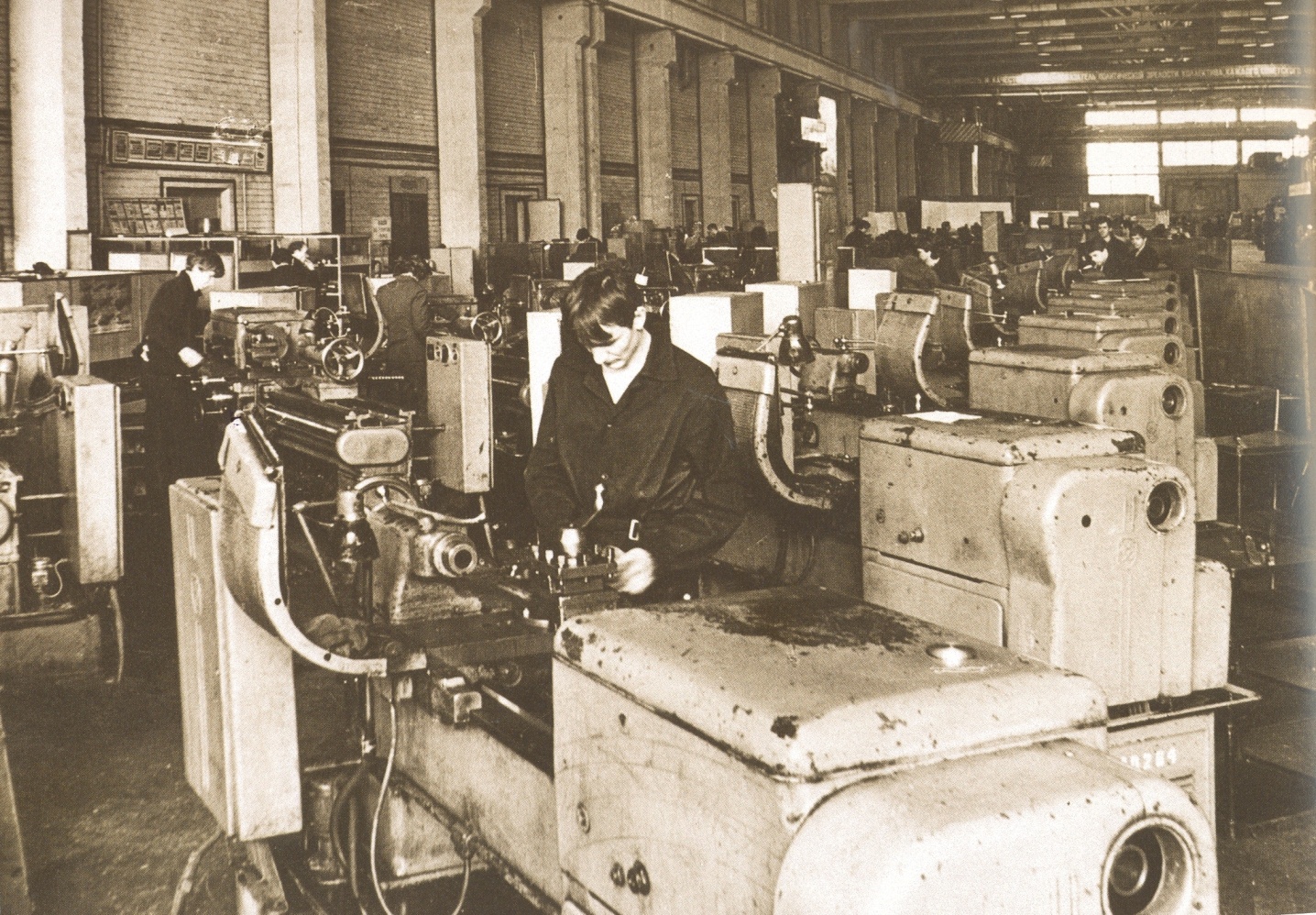

And what is happening in reality? In reality, for several years now, the process of squeezing the last juices from the company before the final collapse is underway and near to finish. This is how factory workshops looked in its best years.

Work was in full swing, production was developing, more than three thousand employees worked at the shipyard. And in this state the hull workshop today.

Empty, quiet, half-plundered space. This milling machine has already been dismantled and is ready for loading out:

When you see this photo, the machine will already be gone and sold, possibly for scrap metal. The shipbuilding workshop has an even more depressing picture. Here the process of destruction is near to completion. Machine tools, technological equipment, assembly beds were cut in the most barbarous way and scraped.

But once upon a time hulls of new ships have been built here.

That’s how the improvement, increase and reconstruction of fixed assets actually happens. How did the plant reach such a state? What kind of enemies brought this prosperous enterprise to decline?

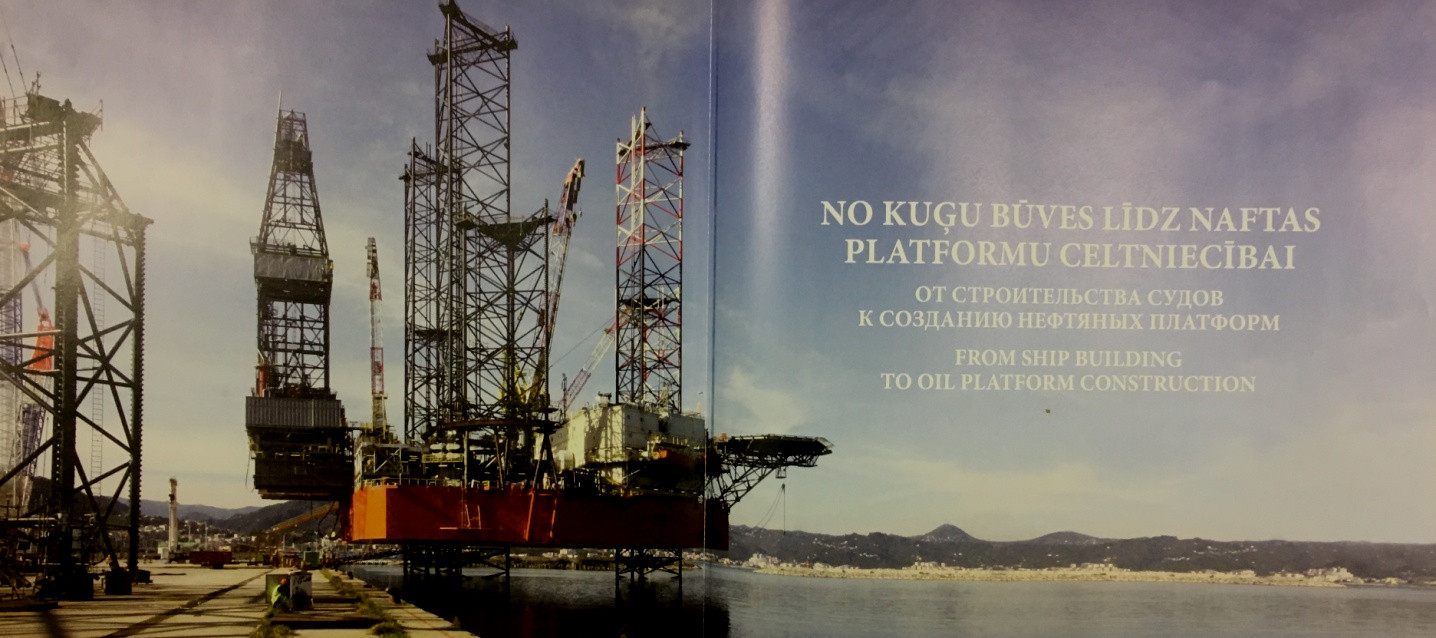

Let me introduce him: the actual owner, an effective manager and a progressive capitalist. Just a few people manage to collect such a bouquet from publications on websites kriminal.lv and kompromat.lv, how did this succeed Vasily Melnik. Retelling them is a fascinating, albeit ungrateful occupation. Because this is not about a person, but about a system. A “businessman with a dubious reputation” was an adviser of two Prime Ministers and one President, and once even served as Minister of Economics for three days. He received the Order of Three Stars from the hands of President V.V. Freiberga and the Order of Friendship of Peoples from the hands of President V.V. Putin, while happily avoiding the fate of becoming a Kremlin agent. He has held and holds high positions on the boards of many companies. He enters the offices and living rooms of many senior government officials. He is an important gear in the mechanism of state power. And this gear, smoothly spinning in engagement with others, richly greased with babbling financial flows and polished for many years of successful operation, has led the shipyard to such a sad outcome. Perhaps the transformation of the plant from a profitable enterprise into half-ruins began with this wonderful project.

Drilling platforms were built in Singapore, were purchased through a series of dummy one-day firms for the Ukrainian Neftegaz, and today they operate on the Black Sea shelf. Not a single bolt for them was machined at the Riga shipyard, not a single weld was made by the hand of a Latvian welder, not a cent was received in the Latvian budget from this transaction. But some Ukrainian corrupt officials and oligarchs became richer, and Vasily Melnyk bought a casino in London for 15 million pounds. Around this time, the first signs of turmoil began: broken contracts, delayed salaries to employees, lawsuits with subcontractors. And you can’t write it off for any crises and market conditions. Ship repair is still a demanded business. Among its Polish, Lithuanian and Estonian competitors, the Riga Shipyard had significant advantages and good starting opportunities. They say that when the owner of BLRT Grupp, Estonian businessman Fyodor Berman found out that his main competitor was losing his position on his own, he could not believe his ears. His company successfully intercepted the Latvian market sector. The BLRT Grupp, established on the basis of the Baltic Shipyard, expanded, received new orders, and acquired the Finnish shipyard in Tartu. The largest 30 thousand tons capacity floating dock of the Riga shipyard has also been sold to this company and will soon be towed to another Berman’s shipyard in Klaipeda. They are already considering the other two floating docks, the last major valuable equipment of the Riga Shipyard, after the loss of which ship repair will become completely impossible.

Currently the Company is in the process of legal protection. Just in case, this is such a status that allows the company temporarily not to pay debts, to stop forfeits in order to restore solvency, revive production and again begin to act effectively. Above, we saw how the shipyard is “being restored.” In fact, the owner received a reprieve for the quiet completion of its plunder. Vasily Melnik’s daughter, who is currently managing the plant, with her blatant incompetence, as well as with “exquisite” manners, is perfectly suited for this role.

In order to crank up the destruction of such an important industry for Latvia, the connivance of many state bodies, up to the highest ones, was necessary. This precedent harmoniously fits into the economic policy of those people that are in power today. Shipbuilding followed the sugar industry, metallurgy, fishing, transit, and other sectors of the real economy. The Latvian collective capitalist, who came to power and gained strength on privatization, capture, destruction, corruption under the smokescreen of nationalism, was incapable for constructive activity, development, progress. One after another “flock obliquely” leaves Latvia, dreams of its own “Nokia,” of “filling up Europe” with its high-quality products, of economic independence and, at the end, of the very independence that Atmoda’s nightingales have told us so much about.

You can read about some details of the shipyard history in our earlier article “Riga shipyard goes to the bottom.”